Our boat was only half a dozen miles out of St Mary's, the main island in the Isles of Scilly , but the sea had become a different beast entirely. The waters that lulled against the harbour walls were long gone, and as we arced around the Western Rocks – a notorious cordon of razor-sharp skerries at the very south-westerly reaches of England – the swell surged. Waves slapped against the bow as the boat keeled to and fro. The water was the colour of midnight, and I peered into the darkness for a sign of the HMS Association, one of 1,000 shipwrecks that lie splintering into the seabed around Scilly.

Two parallel reefs, much of which is submerged at high water, the Western Rocks posed a formidable threat to sailors bound for safe harbour in Tresco or St Mary's. And the names that each cluster of jagged granite has been given over the years – Inner Rags, Tearing Ledge – hint at the devastation wrought.

"It is doubtful if any collection of rocks in the whole of the British Isles has a worse reputation," said Richard Larn OBE, president of the International Maritime Archaeological & Shipwreck Society and author of Sea of Storms: Shipwrecks of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly . "This immense area of hidden danger has been the setting for the worst of the many wreck disasters on Scilly." None, though, have been more tragic, nor played a more significant role in history, than the sinking of the Association in the early years of the 18th Century.

A 90-gun, second-rate English warship, HMS Association was the flagship of Sir Cloudesley Shovell, who had worked his way up from lowly cabin boy to become Admiral of the Fleet in 1705. Shovell had distinguished himself in the Nine Years' War and in early skirmishes of the War of the Spanish Succession, but after a summer spent (unsuccessfully) laying siege to the French port of Toulon, he set sail for home, departing from Gibraltar for England in late September 1707.

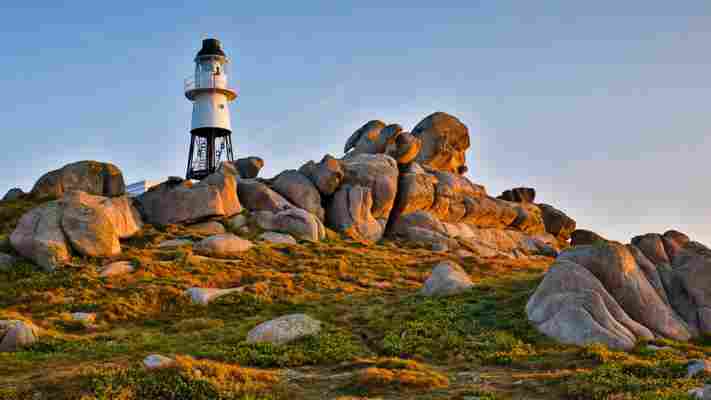

Surrounded by treacherous rocks, the Isles of Scilly have one of the highest concentrations of wrecks in the UK (Credit: David Chapman/Alamy)

At around 20:00 on 22 October 1707, believing they were off the coast of Brittany and heading into the English Channel, the fleet ploughed on through the darkness and straight into the Western Rocks. The Association, under the command of Captain Edward Loades, struck the Outer Gilstone rock and sank within two minutes. Three other ships – the Eagle, the Romney and the Firebrand – were also wrecked. "The Weather being very hazy and rainy and Night coming on dark…some of them [were] upon the Rocks to the Westward of Scilly before they were aware. Of the Association not a Man was sav'd," reported the Daily Courant, Britain's first daily newspaper, at the time. Some 1,450 men were lost across the four ships, with only 24 survivors between them. It remains one of the worst disasters in British maritime history.

It is doubtful if any collection of rocks in the whole of the British Isles has a worse reputation

So how did the finest seamen of his age – as famous in his day as Lord Nelson was in his, according to Larn – get so completely, and catastrophically, lost? Foul weather didn't help, nor did the low-lying nature of the Scillies and their fringing reefs, which blend into the water's surface at night and in poor visibility. Analysis of the log books from the ships that did make it back to London also revealed the fleet's officers were using charts that misplaced the Isles of Scilly eight nautical miles to the north.

All these issues were compounded by the real problem – that in the early 18th Century, there was no accurate way of determining a ship's exact longitude (its east–west position) at sea. Sailors used a process called "dead reckoning", measuring speed, direction and distance to estimate their location. But it was an educated guess at best. Shovell and his officers knew they were aligned with the English Channel but could never have known which side of the Scillies they were.

You may also be interested in: • Britain’s Mediterranean-like isles • The shipwreck that birthed a nation • The tiny isle with a wild, lawless past

Losing the Admiral of the Fleet and so many men alongside him, "stirred public opinion [and] was quoted as an illustration of the urgent need of a means to find longitude at sea," wrote curator Lieutenant-Commander David Waters in the catalogue for 4 Steps to Longitude, an exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in 1962. Larn goes a step further, believing that parliament introduced the Longitude Act of 1714 as a direct result of the disaster. The act offered a reward – the Longitude Prize – of £20,000 to whoever could produce a solution that was "practicable and useful at sea". Sir Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley (of comet fame) set their minds to the task, but the problem was eventually solved by a carpenter-turned-clockmaker from Yorkshire.

It took John Harrison 25 years and four attempts, but in 1759 he invented a marine chronometer that allowed a ship to calculate its longitude by comparing the difference in local time at sea with the time in Greenwich. His prize-winning pocket watch, known as H4, overcame the challenging conditions on board – the issues of motion and variation in temperature – and offered the stability required.

"H4 works in principle just like any other mechanical watch," explained Emily Akkermans, curator of time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London. "But the difference is the level of precision [Harrison] achieved by using a 'high energy' balance that would beat faster than the smaller and lighter ones found in traditional watches."

H4, John Harrison's marine chronometer, solved the problem of calculating longitude while at sea (Credit: Wilf Doyle/Alamy)

In a four-month test voyage from Portsmouth to Jamaica, H4 was found to be just 1 minute and 54 seconds out. And yet the Longitude Board refused to fully recognise Harrison's achievement and he never received the full amount of prize money he was owed.

The Association, meanwhile, still lay scattered beneath the Outer Gilstone, as she would for another 200 years. In 1963, Larn, then a Chief Petty Officer First Class in the Royal Navy, initiated the search for the wreck when he approached an admiral to ask if he could borrow a minesweeper. It took Larn and a team of divers from the Naval Air Command Sub Aqua Club (NACSAC) three years to find the Association, but on 4 July 1967 they discovered a bronze cannon and gold coins on the Gilstone Ledge.

In just six weeks, they raised several French cannons from the seabed – trophies from the War of the Spanish Succession (one of which they donated to the Valhalla Museum on Tresco) – along with gold and silver coins, pewter plates and a phenomenal assortment of artefacts, from buckles and buttons to candlesticks and combs.

Word quickly got out, though, and amateur salvagers descended on the Scillies. "Anybody with a diving cylinder and a bedroll turned up here," Larn told me. "There was nothing to stop anybody from looting the wreck of the Association after we left, and that's exactly what happened. Coins were so plentiful that people were paying for pints in the pub with them."

No official record was ever made of what was hauled out of the sea, and within months the findings were dispersed across the globe. A silver plate inscribed with Sir Cloudesley Shovell's coat of arms was sold to Rochester Town Hall where the admiral had served as local MP; artefacts from the wreck now decorate a pub in Penzance; and fragments of the ship's bell were auctioned off to private collectors in the United States.

A stone memorial marks where Sir Cloudesley Shovell's body was washed up from the wreck of HMS Association (Credit: Michael Grant/Alamy)

"What happened on the Association was a national disgrace," said Larn, who was moved to petition his local MP to consider a bill to protect historic wrecks – the Mary Rose had recently been discovered in the Solent and Larn feared her treasures would go the same way if nothing was done. The Protection of Wrecks Act was passed in 1973, a second act of parliament, more than 250 years after the first, which safeguarded wrecks from unauthorised interference. There are currently 24 protected wrecks in UK waters, three of which lie off the Scillies; the Association, whose wreck site still holds scores of iron cannon, is one of them.

While visitors can't access the wreck site itself, they can see some of the items that have been salvaged from the Association at the Isles of Scilly Museum's shipwreck collection, which includes a cannon from the ship and what is believed to be Sir Cloudesley Shovel's crumpled "po" (or potty).

The museum was forced to close in June 2019 when its historical home was deemed unsafe, and the collection is currently spread across the Town Hall on St Mary's and in interim pop-up exhibitions on the off-islands of St Martin's, Tresco, Bryher and St Agnes – in hotels, shops, community halls and even an old telephone box. "We're trying to reconnect object to place, and to keep the museum alive while we fundraise for a new home," said Kate Hale, the museum's curator, of her Museum on the Move project . Hale had been in the job for just two months when the museum closed overnight; lockdown was in full swing, so Covid restrictions meant she had to work on her own, in an unlit basement, wrapping up 10,000 objects from the museum's archive by torchlight.

What happened on the Association was a national disgrace

Visitors can also experience the wreck via the new Walking Companion app , also created by Hale and her team and developed as part of the Coastal Timetripping project. The mobile app automatically activates when you're within range of a nearby shipwreck and allows visitors to explore, via augmented reality, the remains of the Association.

Down among the yellow-horned poppies on Porth Hellick, for example, seven miles from the site of the wreck, a memorial marks the spot where Sir Cloudesley Shovell's body was "flung on the shoar and buried with others in the sands". He had been washed up here with his two stepsons, his captain and his pet greyhound, Mumper. Stroll around the cove and the app will pop with paintings of the Association, images from the Isle of Scilly Museum's archives and 3D models of the ship's bell. A local theatre group reads out a poem depicting events on the night of 22 October 1707 by the Scillonian poet Robert Maybee, and Cornish folk group Dalla sing a haunting ballad covering the legend of the wreck.

And out past the cove, beyond the island of St Mary's, the ocean continues to rush and rage around the Western Rocks.

St Mary's is the Isles of Scilly's largest island and the closest harbour to the notorious Western Rocks (Credit: Westend61/Getty Images)

Hidden Britain is a BBC Travel series that uncovers the most wonderful and curious of what Britain has to offer, by exploring quirky customs, feasting on unusual foods and unearthing mysteries from the past and present.

--

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Leave a Reply