Article continues below

São José Paquete d’Africa lies beneath the waves of Clifton Beaches in Cape Town (Credit: Werner Hoffmann)

The first known shipwreck of enslaved Africans to be studied and now excavated lies beneath the waves of one of the world’s most popular beaches in Cape Town, South Africa. Called the São José Paquete d’Africa , the wreck went undiscovered for more than 200 years.

Finding the São José was “somewhat of a detective story,” explained marine archaeologist Jaco Boshoff of South Africa’s Iziko Museums . Boshoff and his partner, Dr Steve Lubkemann from George Washington University in the US, are co-principal investigators of the international Slave Wrecks Project , a global archaeological and research effort that started in 2008.

The project set out to find the São José based on archival documents of the Dutch East India Company (which governed the Cape Colony until 1795) found in the Western Cape Archives and Records Service . These documents told the story of a Portuguese slave ship with 512 Mozambican slaves destined for Brazil that sank on 27 December 1794 in Camps Bay on the Cape Peninsula. Boshoff and his team started diving the area in search of the wreck, but found nothing.

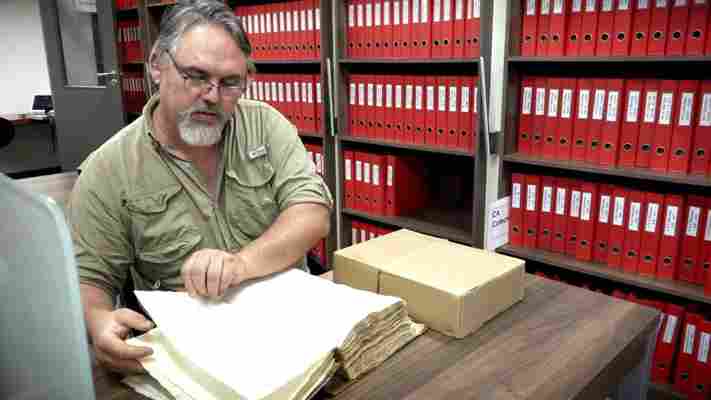

Jaco Boshoff: Finding the São José was “somewhat of a detective story” (Credit: Werner Hoffmann)

Out of sheer desperation, in 2010, Boshoff went back to the Cape Archives, which preserves records from 1651 when Cape Town’s first Dutch colonial settlement was established. There, he discovered the Portuguese captain’s account of the wreck, which was translated into Dutch by a government official employed by the Dutch East India Company.

Having studied Dutch – and being an avid diver around the Cape Peninsula – it dawned on Boshoff that the captain’s description of seeking shelter against the wind ‘onder de Leeuwe Kop’ (under the Lion’s Head) meant it was more plausible for the wreck to have occurred at the Clifton Beaches, which lie below Lion’s Head, a mountain resembling the head of a crouching lion next to Table Mountain.

Boshoff also realised that a wreck discovered by treasure hunters at the Clifton Beaches in the early 1980s identified as the Dutch vessel Schuilenburg, which sank in 1756, was in all probability misidentified and could in fact be the São José. Boshoff and his team then focused their attention on the Clifton Beaches.

Iron ballast bars were found at the Clifton wreck site between 2011 and 2012 (Credit: Rodger Bosch/Stringer)

An archival document found in the Arquivo Historico Ultramarino archive in Lisbon, Portugal, by Dr Lubkemann states that the São José left Lisbon on 27 April 1794 for Mozambique via Cape Town with 1,400 iron ballast bars in its cargo. According to Boshoff, the members of the Slave Wrecks Project think the bulk of the bars were used to pay for slaves from Mozambique, but some were left on board to offset the weight of the human ‘cargo’ on the ship.

On 3 December 1794, Captain Manuel Joao Perreira sailed from Mozambique for Brazil’s Maranhão state. Perreira was planning a stop in Cape Town to take on provisions before crossing the Atlantic, where he intended to sell the 512 slaves. However, the ship ran into trouble off the Cape Peninsula and foundered. More than 200 slaves died, while the survivors were sold into slavery in Cape Town.

When Boshoff and his team found iron ballast bars at the Clifton wreck site between 2011 and 2012, it was the evidence they had been looking for. They started to document the wreck fully starting in 2013, bringing artefacts to the surface in 2014. “Slowly we uncovered more and more evidence,” Boshoff said. “By using CT scan technology – because of the fragility of the artefacts – we identified the remains of slave shackles covered in hardened sand sediment.”

The ballast bars, as well as other items such as a portion of the hull that was removed from the wreck site, are currently on loan and exhibited at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC.

Jaco Boshoff: “Slowly we uncovered more and more evidence” (Credit: Iziko Museums)

This discovery is significant because there has never been archaeological documentation of a vessel that foundered and was lost while carrying a cargo of enslaved persons,” said Lonnie G Bunch III, founding director of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

Clifton’s four beaches have been popular with sunbathers for decades (Credit: Werner Hoffmann)

Overlooked by some of South Africa’s most expensive real estate, Clifton’s four beaches – simply named First, Second, Third and Fourth – have been popular with sunbathers for decades due to their protection from the Cape’s howling south-easterly winds by Lion’s Head.

Despite the area’s perceived exclusivity, however, the beaches have always been accessible to everyone, having been some of the only beaches that did not display racial segregation signs during the country’s apartheid era.

While many Clifton residents are unaware of the São José wreck site located mere metres from Second and Third beaches, one well-known resident has been following the work of the Slave Wrecks Project after hosting a memorial ceremony, in 2015, at his house overlooking the site. Former anti-apartheid activist Justice Albert Louis Sachs (known as Albie), is one of the writers of South Africa’s first democratic constitution and was appointed by Nelson Mandela to serve as a judge on South Africa’s Constitutional Court.

A resident of Clifton, Justice Sachs sees the relics of a slave ship so close to an idyllic beach as a reminder of a dark history. “And it’s not just our history; it’s the history of the world,” he said. “I think the value of these kind of discoveries is that they are being undertaken by people from all over the world… in a concerted international effort to understand, and reveal, and respond to, and even take a kind of responsibility for, what was an international form of depravity.”

A permanent exhibition on the São José will open in the Slave Lodge history museum (Credit: Hemis/Alamy)

Nancy Child, an artefact conservator, left her job at the University of Oslo’s Cultural Heritage Museums (where she worked with artefacts found on waterlogged Viking ships) to preserve items retrieved from the São José wreck site.

One of her most challenging tasks was to conserve the slave shackles found at the wreck. Due to the high level of water corrosion and the hardened sediment covering the shackles, Child had to use the process of electrochemical and electrolytic reduction cleaning, which is done by placing the artefacts in an electricity-conducting solution (electrolyte) and running a low electric current through them. While this process can take years to bear results, it is possible to reduce enough of the ferrous corrosion compounds back to a metallic state.

Her immediate aim is to ready some of the artefacts – such as the shackles, as well as nails and cladding used for the ship's construction – for a permanent exhibition on the São José that will open on 12 December 2018 in Cape Town’s Slave Lodge history museum. Built in 1679 to incarcerate slaves, the building is one of Cape Town’s oldest and has now been renovated (after serving as government offices for more than a century and a half) to house exhibitions about South African history under the umbrella theme, ‘From human wrongs to human rights’.

Gerty Thirion: "“A shipwreck is a time capsule. It’s a message in a bottle" (Credit: Iziko Museums)

A shipwreck is a time capsule. It’s a message in a bottle. We need to preserve the artefacts and study it meticulously,” said Gerty Thirion, collection manager of the Slave Wrecks Project.

Documenting slave shipwrecks offers a new way to study the global slave trade (Credit: Werner Hoffmann)

Searching for and documenting slave shipwrecks offers a new way to study the global slave trade. But this type of research is just one step in achieving the overall goals of the Slave Wrecks Project, said Boshoff. “The project also uses exhibitions and public displays, and employs a variety of other platforms such as art and poetry in its effort to allow a global public to experience and grapple with authentic pieces of this past that played such a foundational role in shaping world history.”

For this reason, the Slave Wrecks Project asked Dianna Ferrus, a Cape Town writer and poet who traces her ancestry to people enslaved and brought to the Cape from Mozambique, to write a personal poem humanising this history. As she details in her powerful poem, it was the custom of the time to name slaves after the month in which they were sold, and some of the South African descendants of the Mozambican slaves today have the surname ‘February’, which strengthens a theory that they were sold less than two months after the disaster.

While the team is still searching for the archival documents of what exactly happened to the surviving Mozambican slaves at the beginning of 1795, Boshoff says they believe that they were sold to work on farms in the Cape Colony shortly after the ship wrecked.

All descendants with Mozambican heritage in South Africa are colloquially referred to as ‘Masbiekers’, a name that originates from the Afrikaans language for a resident of Mozambique (‘Mosambieker’) that was shortened over the years to ‘Masbieker’.

The Slave Wrecks Project hopes to use interactive displays like this carousel (Credit: Werner Hoffmann)

On 2 June 2015, soil from Mozambique was deposited over the São José wreck site to honour those who lost their lives or were sold into slavery. The South African government has subsequently decided to declare the site a national monument. A plaque with information about the site and its historical significance will be erected on Clifton Second Beach. Details will be announced on 12 December 2018.

In addition to physical artefacts, the Slave Wrecks Project hopes to use interactive displays like this carousel (pictured) at the Slave Lodge, which lists the names of slaves that arrived in the Cape Colony. The aim is to make the public more aware of the cultural impact of the slave trade on communities and history. Some visitors might even recognise the origin of their own surnames.

“The story of the São José is the story of just one ship, but it is like thousands of other voyages,” Boshoff said. “Ultimately, the São José compels us to confront and remember the brutal practice of the slave trade and to acknowledge its role in shaping the world in which we live.”

(Text by Piet van Niekerk; video and photos – unless otherwise noted – by Werner Hoffmann)

Leave a Reply